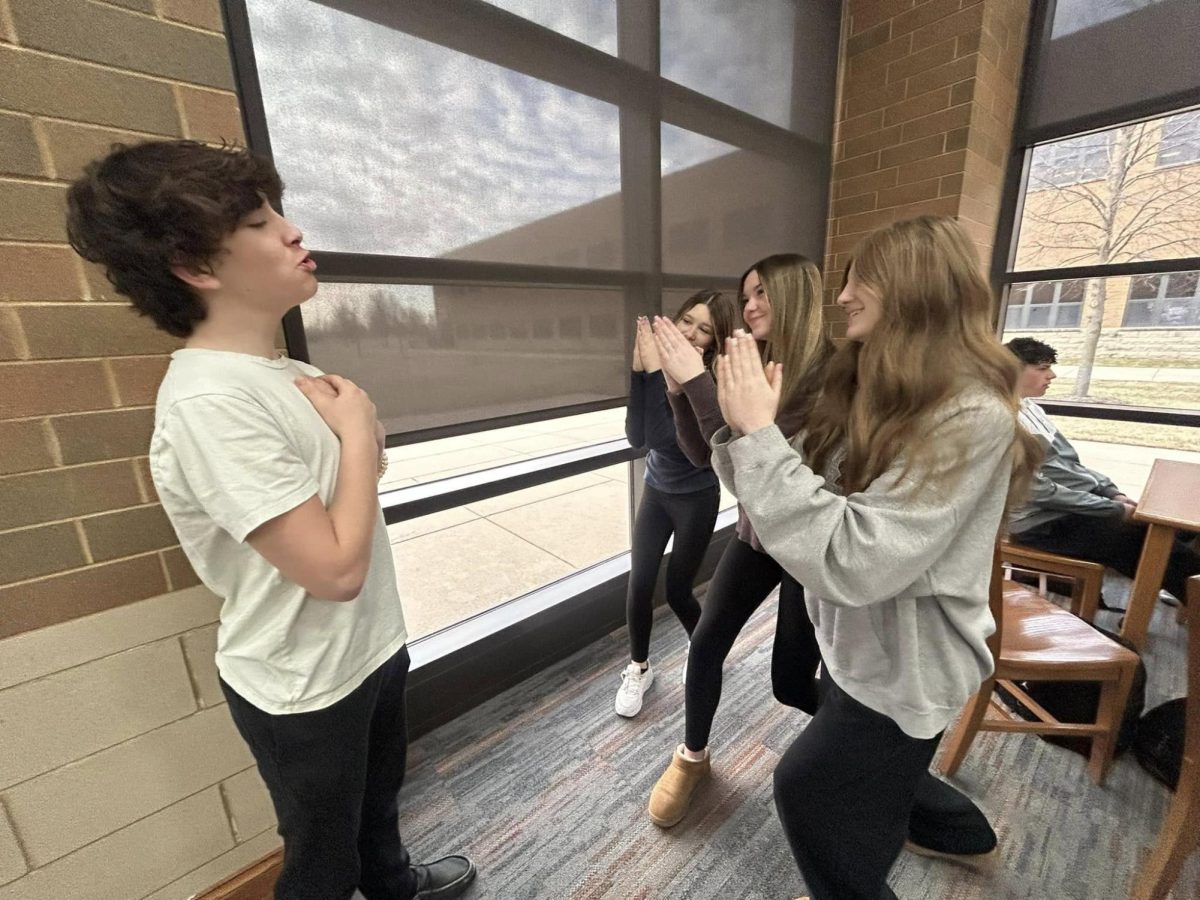

It is Christmas Eve, 1914. It had been 179 days since Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Bosnian Serb student, and 101 days since the crucial First Battle of the Marne concluded. Recently, the once mobile war had slowed down to Trench Warfare, and the hopes of the war ending before Christmas have since dwindled. Now, the armies were waiting for the winter. However, it wasn’t all in high hopes either. Weeks of rain flooded the trenches in Northern France, flooding dugouts, wetting the floors of trenches, and dragging men under. However, on Christmas Eve, the rain stopped, the trenches drained, and now, snow dusted the countryside. That afternoon, the gunfire dwindled, and, in some sectors, had stopped entirely. Concerned about the fraternization over the holiday, Sir John French issued orders that no unofficial armistices would be tolerated. The Germans, however, full of chocolate and cheered by the weather, began to put lit Tannenbaum (Fir Tree) on their parapets, beginning to sing carols, such as the original Austrian version of Silent Night. Lieutenant Sir Edward Hulse, of the Scots Guards, decided they should drown out the Germans with their own singing, which soon merged into a harmony. Some jokingly yelled Christmas greetings, while some stepped out into No Man’s Land to talk. This was happening throughout the entire British Line. Agreements formed, and in some sectors, officers met and shook hands to decide to cease fire the next day, in others, the common soldiers did. Germans shouted across No Man’s Land “English! Tomorrow, if you no shoot, we no shoot.”. At times, it was just one brave soldier, walking into No Man’s Land, waving a newspaper. However, it wasn’t happening all down the line. One British regiment responded to German carols with a burst of machine gunfire while some Germans were killed while attempting to broker the ceasefire. In most sectors, specifically British, since Belgian and French soldiers weren’t too keen on fraternizing with the soldiers who were currently occupying their territory, they held the ceasefire.

British Indian Troops, unfamiliar with Christmas, were reminded of their own holiday, Diwali, were only tempted out by German cigars and cigarettes. And, after a quiet night’s rest, Christmas Day rose. Now the British could openly see the Germans walking on top of their parapets. Soldiers met in the middle on Christmas Eve, but now that dawn broke, it was impossible to ignore the bodies lying between their lines. And so, the soldiers buried their own dead in common graves, grieving in joint services. But that didn’t falter their feelings. Soldiers milled about in No Man’s Land, exchanging gifts from home, their own hats, and even a football game broke out, with a group of Highlanders challenging a Saxon regiment, the latter bursting out in laughter whenever one of the former’s kilts flew up during play. However, not all of it was good will. On both sides, a few used the gatherings to reconnoiter enemy trenches, while both sides used the time to repair dugouts. Of course, for some, this fraternization appeared false. One British soldier flashed his squad mate a hidden dagger, while another refused to smoke German cigarettes fearing that they were poisoned. When one squad of Bavarians discussed whether to meet the British, their corporal snapped at them saying, “such a thing should not happen in wartime. Have you no German sense of honor left at all?” The night before, he refused to join the unit’s Christmas service. Corporal Hitler was odd like that. In some sectors, the armistice came to an orderly close, with officers from both sides saluting and firing their revolvers into the air; a signal the war had resumed. Still other sectors resisted until New Year’s Eve. Nothing like this would happen again as on Christmas Eve, 1915, British officers ordered a 24-hour artillery.

Image: (British troops from the Northumberland Hussars, 7th Division, Bridoux–Rouge Banc Sector)